UPRN address matching algorithm

Overview - Best fit method

The address matching algorithms use a human mediated best fit method to match a candidate address to one address from the set of all available 'standard' addresses.

The algorithms use human semantic pattern recognition, applying rankings of matching judgements following rules that manipulate the text, supported by a few machine based algorithms such as the Levenshtein distance algorithm.

The rankings, which can be considered as a set of numbers, 1-n, could be described as a plausibility measure, as opposed to a probability measure or deterministic measure.

Firstly, some definitions of terms used:

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Candidate address | The address string submitted by a user or a subscriber system for matching |

| Standard address | An address that an organisation, considered to be an authority, has stated as referring to a real location. Typically Ordnance Survey |

Matching a candidate address to a standard address consists of a process whose objective is to reach a high level of confidence that the candidate address refers to the same location as the standard address.

When attempting to match a candidate address to one standard address from a set of standard addresses there are two objectives. If both objectives are achieved, the address is said to be matched. The objectives are:

- To reach a high level of confidence that the candidate address refers to the same location as the standard address.

- To judge that the standard address that has been matched, is probably at least as likely as any other address in the standard set, to refer to the same location.

It can be seen that the objectives include two relative measures, confidence and judgement. A question arises as to whether it is possible for these measures to be mathematically or statistically based, or not.

It does not take long to show the fundamental problem with address matching.

Consider the following candidate and standard addresses

Candidate :Flat 1,15 high street, YO15 5TG Standard :Flat 1,15 high street, YO15 5TG

By any computable measure, e.g. length of string, character position match, it can be seen that these two addresses are identical. One can easily deduce from this that there will be a high level of confidence that they refer to the same location. Also, as it is not possible for any other address to be more similar, a sound judgement can be made that this is the most likely from all of the addresses, except for the other identical addresses in the set.

Consider the following

Candidate :Flat 1 ,15 high street YO15 5TG Standard :Flat 1, 15 high street YO15 5TG

One can see that they are different. Whilst both have the same characters, the position of character 7 and 8 have been transposed. Yet a human being would almost certainly say they refer to the same place. Also, unless there is another address that is exactly the same as the candidate, the match is the most likely.

Consider the following:

Candidate :Flat 1,15 high street YO15 5TG Standard :Flat 11, 5 high street YO15 5TG

Like the above example there has been a transposition at position 7 and 8. Yet they are obviously different addresses. They are very unlikely to refer to the same location unless there were no other flats or numbers on the street. Even If there were no other numbers or flats on the street then the confidence level may still only be moderate. Not enough to match?

So it can be seen that in fact it is semantics that drive matching judgements and not just positional variations and character mismatches. Likewise:

Candidate :15 Flat a High Street YO15 5TG Standard :Flat a 15 high Street YO15 5TG

These two addresses are very likely to be the same unless a closer fit can be found. A closer fit is NOT a closer fit simply by character matching.

Candidate :15 Flat a High Street YO15 5TG Standard :1 Flat 5a high street YO15 5TG

These are also quite close but clearly semantically different.

So it can be seen that in nearly all cases, when comparing one address with another, or an address against a set of addresses, it is the semantic interpretation of the address that determines the match. Human based semantic interpretation is still more reliable than AI for language-based judgements.

It follows that address matching rules are nothing more than trying different addresses on for size and see which one a human being thinks means the same or a similar thing.

Pattern recognition and manipulation

What does the computer do? Basically it computerises the process of human pattern recognition and human suggested string manipulation.

Firstly, we know from our own experience that words that are similar or the same words in different orders often mean the same thing. We also know that letters and numbers can be transposed without too much loss of meaning. We also know that misspelled words when corrected usually mean the same thing.

For example, we make a judgement that the word 'flr', in the context of an address, is likely to mean ‘floor’. In a cookbook though it might mean “flour”. Also we know that the same meaning can have different words or spelling such as '1st', and 'first'. Often different punctuation means more or less the same '5/6' and '5-6' etc.

From this knowledge we can set pattern recognition rules. We can say that full stops can be removed or '/' replaced with '-' because we know that they are unlikely to affect the semantics.

However, there are always twists. It is reasonable to infer that 'st' is likely to be short for 'street'. However, the phrase 'St Katherine's way' implies a saint, not a street. Therefore the manipulation rules must also take account of potentially wrong manipulations. In this case, a 'street' can be recognised by checking the resulting expansion e.g. ('high st -> high street') against a standard street index, or the position of the 'st' in the string. These patterns and manipulations are coded and validated and adjusted if wrong manipulations are discovered.

Human judgement based manipulations can result in false positives. As the algorithms are developed the introduction of false positives must be checked regularly and the manipulation rules adjusted.

Rules,based on knowledge of the world can be quite clever. Knowing that a “top floor flat” is more likely to be the same as “flat c” from a list of a, b, c than “flat a”, gets a preference from a set of options.

Address components

Addresses have more than a dozen semantically different components. Name of a flat, number of a flat, number and letter of a flat, range of numbers for a flat, a building name, a building number, a building number and letter, a range of numbers with or without letters, a dependent thoroughfare, a street, a dependent locality, a locality, a town, a city and a post code. On top of this there are the descriptions in relation to the front or back of the building, the level within a building or whether facing east or west, north or south. There are many words to describe flat like units, maisonettes, studios, houses, apartments and so on.

With address labels with up to around 10-12 semantically different field meanings and with human tendency to place words in the wrong fields and in the wrong order in the wrong fields, or inadvertent field separators means that field allocations cannot be relied on. Manipulation rules take account of wrong allocations. In some cases users submit addresses with everything in one field. Manipulation must take account of having no user determined address fields at all.

With each manipulation comes a human judgement that the resulting string is still a true reflection of the candidate and that a match to a standard would be correct. It is only human judgements that can be used to match addresses.

There are a few useful mathematical techniques. Pluralisation and de-pluralisation. Use of Levenshtein distance algorithm with allowable distances roughly proportional to the length of the words can help. Partial matching of words with front part matching (as humans often get the end of phrases wrong rather than the start) helps also.

However, these are just techniques to speed up what would otherwise be a manual process relying on eyesight, concentration and a high boredom threshold.

Conclusion on approach

A computer only speeds up the process of pattern recognition and string manipulation that would otherwise by done by a human being, each manipulation being specifically undertaken with a view to enable a visual check that would result in a match.

If a particular manipulation falls short of something that a human knows would match, the manipulation is abandoned and another one tried. The usual approach is to start with part of the address that seems to match, make small manipulations initially, then if no matches are found, increase the degree of manipulation. There is no useful machine-based algorithm based on purely mathematical functions. Whilst a mathematical function like transpositions may highlight likely character matches (and there is an association between character matching and semantic meaning) relying only this approach would reduce possible semantic matches achieved by larger distance comparisons using human judgement.

The most significant problem is what to do when manipulations build on manipulations that are already dubious. In this case the level of confidence drops at this point and the process can start again from a different starting point, repeated until the algorithm author has judged that one set of manipulations give higher confidence than another. This results in a series of rankings for each set of manipulations. If the rankings are in the wrong order, then a premature match might be made, resulting in a false positive match. Adjusting the ranking uses the same type of judgement as adjusting the manipulation.

Address matching processes

Firstly some of the terms used are defined. This table lists the main terms used in the description

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Subscriber | An organisation (or system that is operating on behalf of an organisation) that is seeking to access data from the Discovery service |

| Standard address | An address provided by an authoratitive body that has got an assured link to a UPRN |

| Candidate address | The address string submitted by a user or a subscriber system for matching |

| UPRN | Unique Property Reference Number as supplied by Ordnance Survey |

| AddressBase Premium | Ordnance Survey comprehensive database holding the UPRNs and several addresses for each |

| Equivalent match | The UPRN is deemed to be equivalent to the property as described by the submitted candidate address |

| Sibling match | The UPRN is assigned to a property nearby e.g. next door |

| Supra-property match | The UPRN is assigned to a higher level property than the submitted address.

For example if the submitted address was flat 1 and the UPRN was assigned to the parent building then this would be a supra-property match |

| Sub-property match | The UPRN is assigned to a lower level property than the submitted address.

For example if the submitted address was flat 1 and the UPRN was assigned to flat 1a then this would be a sub-property match |

| DPA file | The Royal Mail Delivery Point Address file |

| LPI file | The Local Property Identifier file |

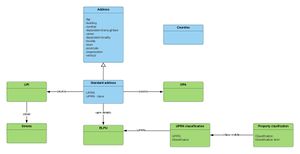

The standard address database

Source and nature of standard addresses

The Ordnance Survey (OS) has a product; ‘AddressBase Premium (ABP)’ which contains information about every UPRN. It contains three main files, with each entry in each file assigned directly to a UPRN:

- A Delivery Point Address file (DPA) which lists all the Royal Mail addresses sourced from Royal Mail’s PAF (Postcode Address File) which is a non-geocoded list of addresses that mail is delivered to.

- A Land Property Identifier file (LPI) which lists geographical addresses as maintained by contributing Local Authorities. They represent the legal form of addresses as created under street naming and numbering legislation. The structure of a geographic address is based on British Standard BS7666.

- A Basic Land Property Unit file (BLPU) which lists all the unique properties, UPRN, post code and geographical coordinates.

There can be more than one version of the LPI geographic address for a UPRN, capturing approved, alternative, provisional and historical (inactive) versions of the DSI exclude status 8. All are included as potential matches.

These files are considered as the standard address details for each UPRN. Whilst each file represents addresses in a slightly different way, they are aligned with each other. The LPI file contains entries that are often more granular than the DPA file. Some UPRNs only exist in the LPI file and not in the DPA file and vice versa. Thus the LPI file can usually be considered as the more definitive of the two but a match to either can be considered correct.

In addition to a difference in the level of detail in the two files there is sometimes a relationship between one UPRN and another in that one UPRN can be a “parent” UPRN of a more detailed property. For example a parent UPRN may be assigned to a building whereas a child UPRN is assigned to a flat within a building. Both the parent and the child UPRN may exist in the DPA file and the LPI file.

In effect this means that there are two sources of the truth for an address, and matching to either source provides the UPRN. It is important to map to a child UPRN where possible as the lowest level detail better represents actual households.

Loading addresses, formatting, indexing and custom indexes

Addresses are loaded into the database from source (see green classes).

Each source standard address is reformatted into a standard address object, which is an instance of a class that extends the address class by dint of having a UPRN and status. The objective of the reformatting is to produce a single model of an address for matching to which candidate addresses will also adhere.

Format also includes standardisation of the use of suffix and ranges e.g. 1-2, 1a, 1a-1f.

Formatting of the standard address also includes 'fixing' some errors and removing some extraneous words that are unnecessary in the matching process. These include:

- Spelling corrections, modified by context

- Replacement or removal of punctuation and lower casing

- 'Flat' removals, involving the removal of terms from the flat field that signal a flat are can be considered equivalent e.g. flat, apartment, towers, rooms, flat no, unit workshop, maisonette. Some special flat terms are retained for potential removal later in a leaf manipulation e.g. 'studio'

Addresses are then indexed in a number of ways:

- Secondary index on post code street and building name columns

- Multiple Composite indexes on post code, street, number, building flat & post code building & building flat and post code

- Functional indexes on the above including concatenation, de-pluralisations

Once Loaded, reformatted and super-indexed. The address database is ready to be used.

Candidate address pre-formatting

It is assumed that an address is submitted as one or more delimited fields with the post code at the end if available.

Optionally, an area based qualifier is included, which is useful if there is no post code. For example a practice post code or simply a list of major postcodes. These narrow down the options when checking against 100 million+ addresses.

Candidate addresses are subject to the same reformatting rules as standard addresses (spell checking etc). However this needs to be done in two stages

- Before the address fields are populated

- Once more after the address fields are populated

Using human example driven pattern recognition a set of manipulation rules are followed that result in an address object being populated. There are hundreds of rules to follow. Many rules manipulate data when new patterns are recognised following from previous manipulations.

For example, Let us assume the following pattern and manipulation occurs

flat 1 St Paul's house 15 high street

Pattern recognition= street preceded by number manipulation = populate number and street

number_street = 15 high street

However, consider a different example that requires additional manipulating

flat 1 St Paul's house 14- 15 high street

Pattern recognition= street preceded by number manipulation = populate number and street resulting in

number_street = 15 high street

Which is wrong, and therefore a subsidiary pattern of two numbers, with or without a dash, making sure that there is a flat number already allocated, and the number street is therefore

number_street= 14-15 high street

Iterative Pattern recognition together with manipulation results in >100 variations which never complete the number of possible manipulations needed.

The curve of the number of manipulations needed to improve the match detection rate by a certain percentage is exponential.

Matching candidate to standard addresses

Match failure circumstances

It is not always possible to match a Discovery address exactly to a specific UPRN. There are 3 reasons why a Discovery address may not match

- It is a false address i.e. the address does not actually exist in reality and cannot therefore be matched

- There may not be sufficient information in the candidate address for it to match at the level of detail required.

- The Discovery address may contain more detail than the standard address and is therefore too accurate

There are missing entries in the DPA and LPI file. The files are constantly being updated and released every 6 weeks. There is a massive amount of building going on. Even changes to post codes can occur and the DPA file (which contains the post code) may be out of date or wrong.

Qualified matching

As well as matching to a UPRN there is also requirement to qualify the relationship between a Discovery address and the UPRN. We refer to these qualifiers as “approximation qualifiers” as they mean that the UPRN is geographically close to the property. Each of the main 5 address fields is assigned a qualifier. The five qualifiers are:

- Equivalent match i.e. we believe the property is the property that the UPRN refers to

- Child - Sub- property. The Discovery address represents a sub-property of the UPRN property. For example the Discovery address “flat 1a Eagle house” may only match to the higher level DPA or LPI entry of “Eagle house”

- Parent. The Discovery address represents a supra-property (parent) of the UPRN property. For example the Discovery address ‘1 Angel Lane’ does not have an equivalent in DPA or LPI but ‘flat 11, 1 Angel Lane’ does exist so it matches to a more detailed identifier qualified as a supra-property

- Sibling. The Discovery address may represent a sibling of the UPRN property. For example the Discovery address ‘flat 12 , 1 Angel Lane’ may not exist in either ABP file but ‘flat 11, 1 Angel Lane’ does

- Best match. This means that the algorithm thinks that it has found an entry as being the best match and the correct location. This does not mean it is an exact match, only that it thinks that the user 'candidate address' is the same location as the one that is listed below and thinks it is a better match than others. It may not be the case that it is the best match. Algorithms explain the "best fit" approach which differentiates what the machine thinks is the best match from what a human might think

- Best (residential) match. indicates that the user has attempted to match only on residential properties or those that may be residential or dual use.

- Best (+commercial) match Indicates that the user has included commercial properties in the match algorithm

Qualifiers are assigned in relation to the final post manipulated address match.

It should be noted that approximation qualifiers are used only when the level of matching arrives at the level of a street number or a more detailed approximation to a building or flat. Simply matching to a street is not considered a match and the address.

Match patterns

The following information is provided when there is a match. A match pattern includes the list of 5 fields and for each, how the match was achieved, and a quailifier.

For the purposes of match pattern reporting the 9 main address fields are rationalised to 5. Dependent thoroughfare, dependent locality and locality are merged to street. Whilst town is used as a guide, as it is of little value for matching, it is not included.

For each of the main 5 fields (flat, building, number, street, postcode) the pattern indicates the degree to which each field is matched and indicates the degree of manipulation or field swapping. A match pattern is built up by one or more of the phrases below i.e. may be more than one manipulation per field.

Match pattern indicators can be conceptualised as a language grammar with the fields being the subjects, the manipulation of the field being the predicate and the qualifier as the object.

There are around 12 match terms with around 50 or so theoretical combinations of those terms. For example a candidate field may be dropped to match, and matched as a sibling (ds). Applying these to 5 fields results in the potential of 300 million or so different combinations.

However, with the algorithms being determined by plausibility, not mathematics, only a number end up being used, usually around 200 or so across 100,000 addresses. further restrictions on the combination occur due to implausibility of some field swaps. For example, post codes are never swapped with streets. Streets are not moved to numbers (as this would have occurred during the initial address formatting algorithm).

The following table lists the match pattern

| character | Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| & | mapped also to | indicates a match using more than one candidate field |

| > | moved to | Means that the candidate field was moved to another field to match e.g. number moved to flat |

| < | moved from | Means that the candidate field was moved from another field to match on this field |

| f | field merged | when moved from and to, the fields are then merged to match |

| i | ABF field ignored | ABP field was ignored in order to match i.e. the ABP address contained more precise detail than the candidate but was unnecessary in order to match. This usually means that the candidate field is null |

| d | Candidate field dropped | The candidate field was dropped in order to match i.. the candidate address has more precise detail than the authority address . The ABP address would probably be null |

| a | Matched as parent | The candidate field matched as being at a higher level than the ABP field, for example flat 6 matching to flat 6a |

| c | Matched as child | The candidate field matched as being at a lower level than the ABP field, for example candidate flat 6a, ABP flat 6 |

| p | Partial match | he candidate field was partially matched to the ABP field or vice versa) typically 2 out of 3 words |

| l | Possible spelling error | The candidate field and ABP field were matched using the Levenshtein distance algorithm taking account of mispellings |

| v | Level based match | The level of a flat in a building (vertical from the street) was used to create the match e.g. 2b for second floor b |

| e | Equivalent | The fields are equivalent, albeit not necessarily spelt the same, using various equivalence lists, word swaps, word drops etc |

Poor quality addresses

Candidate addresses are checked for quality. A poor quality address is more likely to remain unmatched, but a quality indicator is assigned whether matched or not. Poor quality indicators include:

- Null address lines. i.e. all address lines are null

- The entire address line is too short (<9 characters)

- The post code is missing

- The post code is in an invalid format

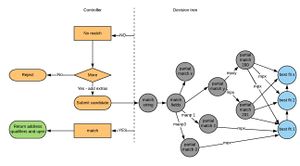

Matching algorithms

Assuming a pre-formatted candidate and a set of standard addresses in the database, the task is to find the best match in the shortest time.

Matching occurs using a decision tree.

A controller object manages the submission of a candidate to the address matching decision tree.

This initially passes on the pre-formatted address. If there is an overall failure it will attempt retries with some modifications to the address. For example, historical addresses often fail. Addition of the word "former" to the start of the address can match with an address marked as "former" in the standard address set.

Decision tree

The match algorithms can be considered as a functional decision tree.

The decision tree can be viewed as a tableaux like truth tree handing a combination of ANDs ORs or NOTS with branching occurring on the OR conditions. The nodes of the trees are pass/ fail tests and the travelling down one of the next branches means a test has passed. If a test fails the process goes back up the feeder branch to the next branching node, and tries the next untried branch, until all branches are exhausted. At that point the feeder branch to the node is now closed and the process tracks back again.

Nodes can be considered to operate in one of two ways:

- Partial match nodes, whereby part of the address, with or without field level manipulation has matched leaving a few fields to match.

- Best fit nodes, whereby various manipulations of the remaining fields are undertaken until either there is a match, or where there are several match options, choosing the best one.

Branches operate in one of two ways:

- Passing on the remaining fields from a partial match to the next node.

- Testing for a pattern in one or more of the fields, manipulating the fields or the content of the fields and passing the reformatted strings to another match node.

From time to time, to enable re-usability, branches end up travelling to nodes that have already been visited having got there by some other route . The second visit will be based on a manipulation that has weakened the partial match confidence levels or more likely has manipulated the field or content data before the revisit.

Ranking of algorithms

Algorithms are ranked (matches are not ranked) by applying two types of judgement

- Confidence that the match is correct.

- Confidence or judgement that it is likely to be the best match from other alternatives

A high ranking algorithm is one where a match is likely to be correct it is most unlikely that a better match exists

For example

Candidate :15 hih st YO15 5DR (note that st would have been corrected) in the preformatting stage) Standard :15 high street YO15 DR

One would expect a high level of confidence that the match is correct. Furthermore, as the only real difference is an edit number of 1, and an exact match with a higher ranking algorithm having already failed, it is a good bet.

Thus an algorithm that matched on post number, building and flat, and a Levenshtein score of 1 would have a high rank.

The other purposes of Ranking is to avoid false positives by repeating previous match algorithms having made more manipulations

Candidate : Flat 41 Lower 2nd Floor 63 Lansbury St. London,E1 6YT Standard :41 ,63 Lansbury street,E1 6YU

This is a two field match. In this example, there is an exact match on the street and number. The post codes are nearby but different. Candidate flat "41 lower 2nd floor" has been stated as supporting '41'. There may have been other matches closer but to get to this point the closer matches would have already been tried. This is therefore a low ranking algorithm.

Best fit algorithms

Best fit algorithms are those that attempt to consider whether one match is more likely to be correct than another match based on a policy decision

For example a question arises as to whether it is better to match on a flat without the building name, than a street number.

Best fit algorithms are end branch algorithms in the Discovery address matching decision tree, attempting a best fit between a candidate address and one from a set of standard addresses, when a prior conclusion has already been made in respect of parts of the address. Typically examples of prior conclusions would be a match on a post code and street.

The algorithms assume candidate address is pre-formatted + spelling corrections, de-pluralised.

Each algorithm consists of:

a) Having narrowed down potential addresses by dint of the prior march assumptions, collect the remaining standard addresses that are potential matches.

b) Ranking them in order of likelihood based on human face validity.

In theory, a best fit algorithm should take account of ALL standard addresses that fit with the prior conclusion. However, this set may be quite large. Therefore a set of assumptions based on face validity of 'potential matches' are made initially, as described below, in order to first rapidly narrow down the results, against which a human judgement can be made. Examples are given below.

Convention is to highlight the candidate dilemma in blue and the correct match in green

Examples of best fit

Candidate verticals

Verticals are descriptions indicating distance from the ground. Algorithm deals with candidate addresses containing vertical descriptions in the flat field. Standard addresses may or may not have verticals.

Example

Candidate :Upper floor flat, 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE | 22a Baker Street, NW1 6XE | 22b Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Prior conclusion :Exact Match on post code, street, null match on building

Algorithm:

Assumes a 'verticals' list in the list store e.g. upper floor, upper floor flat, ground floor, basement, 1st and 2nd floor, etc and each is assigned a 'high' , 'medium' or 'low' vertical qualifier.

Collects all addresses that match by post code and street and either:

a) candidate number / standard number match

b) candidate number/ standard number + suffix match

Flat and number with suffix match

Assuming a located street, the candidate has building number and a flat letter, algorithm matches the candidate flat letter to a standard building number with no standard flat

Example

Candidate : flat b, 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE | 22a Baker Street, NW1 6XE | 22b Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Prior conclusion :Exact Match on post code, street, mutual exact and null match on building

Algorithm:

Simple swap of letter to number suffix, match on building, standard address has null flat.

The building or flat dilemma

Assuming a located street and a matched number, and a matched flat, the candidate has a building name, is it better to match the flat on a standard address without a building (or partial building match) OR better to match exactly on the building and not on the flat?

Algorithm assumes it is better to match on a flat and drop the building.

Example 1

Candidate : Studio 2, the lighthouse, 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : The lighthouse, 22 Baker Street, NW1, 6XE | studio 2, 22 Baker street, NW1 6XE

Example 2 :

Candidate : Studio 2, Sherlock, 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : Sherlock, Baker Street, NW1, 6XE | studio 2, Sherlock Homes, 22 Baker street, NW1 6XE

Prior conclusion: Prior match on post code, street and building number

The building/flat or number dilemma

Assuming a located street match and a candidate with a number , building and flat ,which of the following is the best

- match on post code, street, number

- match on post code, street, building, flat i.e standard address has no number

Example 1

Candidate : Studio 2, the lighthouse, 22 Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : The lighthouse, 22 Baker Street, NW1, 6XE | studio 2, THE lighthouse, Baker street, NW1 6XE

The judgement is 2 is better than 1

Matched on post code and street

If candidate has building and flat then

if match on number then

If matched on post building, flat but Null number in standard then

match

else end branch

else

already matched

else

end branch

Near or exact flat, whether to ignore the standard number

Assuming a match on post code and street. If there is a match on building and flat, but the standard has a number as well as a close match on flat. should it ignore the number and match?

Example 1

Candidate : flat 2a, the lighthouse, Baker Street, NW1 6XE

Standard : , flat 2 , the lighthouse, Baker Street, NW1, 6XE | flat 2a, the lighthouse, 22 Baker street, NW1 6XE

Best fit ranking

The following table lists the best fit algorithm rank orders. As can be seen, generally as expected, an exact or equivalent match is preferred.

The ordering is crucial and sometimes surprising in that a close but wrong post code is preferred to an exact post code but with an incorrect flat.

| Rank | Post code | Street | Number | Building | Flat |

| 1 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 2 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | field merged | field merged |

| 3 | equivalent | equivalent | ABP field ignored | equivalent | equivalent |

| 4 | equivalent | equivalent | candidate field dropped | equivalent | equivalent |

| 5 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | moved to Flat | equivalent |

| 6 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | level based match |

| 7 | equivalent | equivalent | field merged | equivalent | moved to Number partial match |

| 8 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | |

| 9 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | level based match |

| 10 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | partial match |

| 11 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | partial match |

| 12 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | partial match |

| 13 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | partial match | equivalent |

| 14 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | partial match | partial match |

| 15 | possible spelling error | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 16 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | candidate field dropped | equivalent |

| 17 | equivalent | equivalent | candidate field dropped | equivalent | moved to Number |

| 18 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | matched as child |

| 19 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | candidate field dropped | possible spelling error |

| 20 | equivalent | equivalent | moved to Building | field merged | equivalent |

| 21 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | ABP field ignored | equivalent |

| 22 | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | ABP field ignored | matched as parent |

| 23 | partial match | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 24 | equivalent | partial match | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 25 | equivalent | ABP field ignored | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 26 | partial match | equivalent | equivalent | candidate field dropped | equivalent |

| 27 | possible spelling error | equivalent | ABP field ignored | possible spelling error | equivalent |

| 28 | ABP field ignored | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent | equivalent |

| 29 | equivalent | moved from Building | moved from Flat | moved to Street | moved to Number |

Levenshtein distance

Levenshtein distance algorithms are used in determining whether typing errors are likely to be responsible for the mismatch. Rules are applied to test the edit number.

Default positions are:

A distance of 1 is considered acceptable with a minimum phase length of 10. A distance of 2 with a minimum phrase length of 10 is acceptable

A distance of 3 with a phrase length of > 9 would be acceptable

Sometimes the algorithm is used with a parameterised maximum distance and length e.g. post code would be 2, with a minimum length of 5

Fix lists

Fix lists are lists of words or phrases designed to aid string manipulation. There are several fix lists

| List | Description |

|---|---|

| Word correction | used to automatically correct the spelling when used in the context of address matching for example, flt,bst,gdn, cosmopotian |

| Buildings | Indicating that the word implies a building. e.g. Building, house |

| Cities | used in pre-formatting to get rid of the noise of the city when there is a post code |

| Counties | used to remove noise in the pre-formmating |

| Drop words | Words that can be safely dropped when checking for equivalent words e.g. court mews, lane |

| Flats | Set of words that imply a flat e.g. flat, apartment, unit workshop

With a sublist of those that can be removed in lower ranks e.g. studio |

| Flat suffix number equivalents | suffixes "a","b","c","d" and their numeric equivalents 1,2,3,4,5 |

| Floor level equivalents | numbers equivalent to floor level descriptions 1st=1, 2nd=2, basement= 0, first floor = 2 etc |

| Floor term character equivalents | used when testing 'a' for ground floor 'd' = third floor |

| Number word list | One = 1, two = 2, three=3 etc |

| Roads | A list of words implying a road (and therefore might be a street) e.g Road, avenue, lane, park, walk, hill, plaza |

| Swaps | words that can be swapped without change of meaning e.g. apartment-> building, road = street , upstairs = first |

| Towns | List of towns |

| Verticals (levels) | List of terms used to describe distance from the ground and side of building e.g. "upper floors", upper floor", 1st/ 2nd/3rd floor" qualified by direction (low or high) in order to match an "a" for low rather than a "c"

In addition to qualifier of low or high, the verticals may have equivalents e.g. "top" and "upper" , "basement" and "basement floor" etc |

| Best fit rankings | Rankings as described above for ordering multiple matches |